It is hard to imagine an online course without any links to other sources of content on the Internet.

Talk about a wasted opportunity – to have the whole world wide web at your disposal as an instructional resource, and to not tap into that power?

Again, hard to imagine.

What We Know Now

We’ve covered the basic aspects of web accessibility this month, and if you’ve followed along, you should have a pretty good grasp on what it is we should be hoping to find in any accessible web content:

- Headings with logical structure

- Resizable text

- Alternate text descriptions for imaged

- Text transcripts for audio files

- Captioned video in accessible video players

- Color Contrast that ensures easy readability

- Forms with labels and keyboard control

- Page title and language – meta information matters

- Visual focus and keyboard access

- Strobing animations and blinking text

These are all simple aspects of web design that carry a significant impact on the accessibility of the content. There is more to consider before a web page can be considered completely accessible, but satisfying these criteria puts the web content into pretty good standing for being usable if not completely technically accessible.

So let’s look at some of the considerations for checking other people’s web content for accessibility.

We will be making good use of the WAVE tool for today’s activity.

Headings with Logical Structure

Of course we want to have headings in the web pages, but that is not enough. We also want those headings to be used properly in terms of their structure.

One of the quickest ways to evaluate the structure of headings in a web page is to run the page through the WAVE accessibility evaluation tool from WebAIM.

Paste the URL of the webpage you want to include in your course into the Web page address field and press ENTER.

When the WAVE report loads, click on the Structure tab to review the heading structure.

The report will provide an outline comprised of the headings.

If the results don’t look like a proper outline, you know there is a problem with the content.

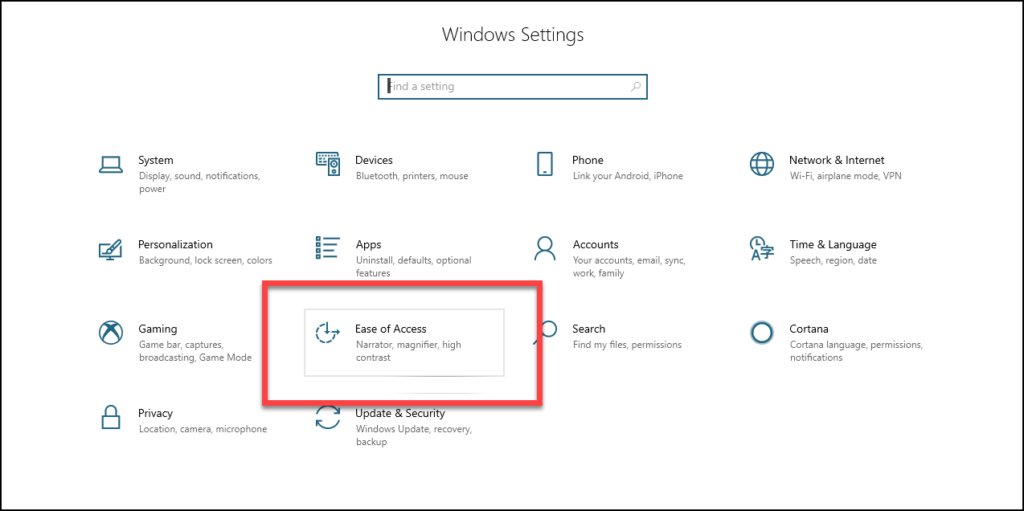

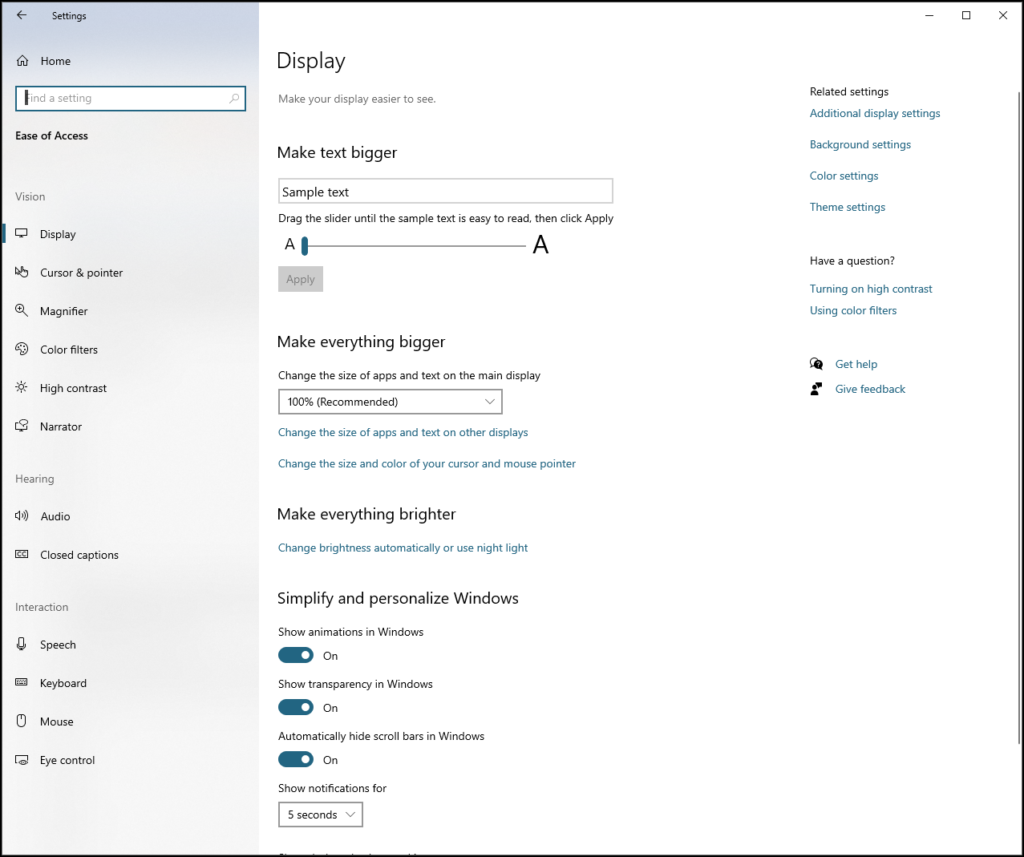

Resizable Text

Another issue that is commonly found in problematic content is that of text that does not gracefully change size.

When people with visual disabilities enlarge the web content to make it easier to see, poorly formatted text will present problems. Sometimes parts of sentences become invisible, or text will wrap on top of other text, or text can grow beyond the size of the layout and disappear.

There are two primary ways to enlarge web page content.

Page magnification enlarges everything, including images and layout elements like space between lines and paragraphs.

Text enlargement only increases the size of the text. It is with text enlargement where you tend to find the most egregious problems.

The specific instructions for text and page zoom vary from browser to browser. Consult your browser help section for guidance in adjusting your settings.

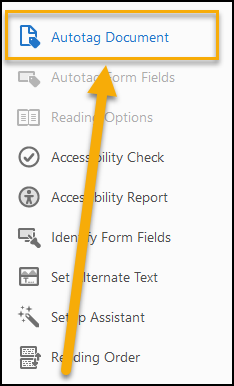

Alternate Text Descriptions for Images

There are two aspects to checking for alternate text descriptions for images.

First is the simple verification that there is any kind of alternate text present in the “alt” tag for the image.

Second is to make sure that if there is a description provided, that it is appropriate and effectively describes the image.

To check a webpage for alternate text descriptions, copy and paste the page URL into the WAVE accessibility checker.

Use the icons generated by the WAVE report to assess the status of the document’s alt text descriptions.

If there are images with missing alt text, WAVE will indicate this with a big red Alt icon, bearing a white stripe down at a diagonal.

If there are images with alt text present, WAVE identifies them with a big green Alt icon, with the word “Alt” written in white. For these results, check the description and make sure that it is accurate and effectively describes the image it refers to.

Visual Focus and Keyboard Access

When you review third-party content to include in your course, always check for the visual focus indicator and do a keyboard check of the basic accessibility of the interactive elements of the page.

TAB between different interactive elements.

Use the ARROW KEYS to explore different options for menus and forms.

SPACEBAR will engage with most form fields that can be checked or activated, and allow you to select an option.

ENTER will activate the interactive element under your focus.

ESCAPE will cancel form entry for the currently focused form field.

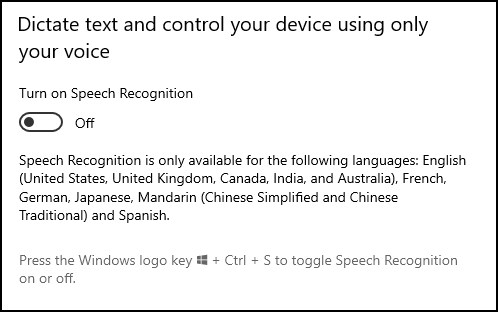

Text Transcripts for Audio Files

If you find any audio files included in the content, check for the presence of a text transcript.

Depending on the audio file format, a transcript could be provided through an associated text file, or embedded into the Lyrics meta-information field.

At a minimum the audio should be accurately represented by the text file.

It is not required for accessibility, but usability is greatly enhanced when the transcript is provided as interactive timed text.

Captioned Video in Accessible Video Players

With digital video, you need to have proper captions that effectively describe the audio content via text.

Play any videos contained within the page and ,make sure there are captions available, and that they are actually representing the audio information accurately.

It is optimal for the captions to be capable of being toggled on or off, but it is acceptable to have captions that are always displayed.

In addition to the presence of captions, ensure that the video is presented through an accessible video player that is keyboard controllable.

Color Contrast for Easy Readability

Color contrast is one of those issues that can have a surprisingly large impact on a lot of different visual disabilities.

The WAVE tool provides a wonderful contrast check as part of it’s accessibility assessment.

Enter the page URL into the WAVE tool and click the Contrast tab to evaluate the color contrast ratio.

Forms with Labels and Keyboard Control

Form fields are interactive elements, and as such they must be operable via the keyboard.

Using the TAB key, you should be able to navigate to any form elements contained in the page.

Using the ARROW Keys, SPACEBAR, ENTER, and ESCAPE, you should be able to verify that the forms are in fact keyboard controllable.

In addition to being keyboard controllable, each form field needs to have a text label that describes the form field.

Sometimes it is possible to have a visual label appear next to a form without actually being associated with the form field. This is an accessibility problem, as someone without sight could end up not knowing what kind of data the form is expecting in that field.

Use the WAVE tool to reveal any forms that are missing labels.

Page Title and Language – Meta Information Matters

One of the invisible aspects of a web page that you need to verify is the presence of a page title and a declared language.

Once again, the WAVE tool makes it easy to find out if either of these elements is missing.

Look for a big red square with a white T in it for a missing page Title.

Missing Language will be indicated with a big red square containing a white globe icon.

Strobing Animations and Blinking Text

There is an unfortunate response to certain frequencies of animation that can cause seizures and narcoleptic reactions. It is important that you do not include any content that has blinking text, flashing text, or animations that create any kind of repetitive or strobe-like effects.

By ensuring the above accessibility concerns are addressed in the third party content you include as part of your online course, you help ensure that your students with disabilities are able to complete the assignments and gain the same educational opportunities as their non-disabled peers.

Thanks for reading!